An Antique Tribal Rug with a Famous Connection

My Shekarlu!

I don’t often write a blog about one particular rug but I couldn’t resist this one!

I have always wanted a rug woven by the Shekarlu tribe, however their rugs are few and far between and very difficult to find. On the odd occasion that one would appear, it would always be way out of my budget.

The Qashqai of south west Persia

The Shekarlu are a high ranking clan of the Qashqai tribe in south west Persia and are named after sugar (shekar), a rare and exotic substance throughout history. Their name literally means “sugar people” which suggests they had access to this prestigious resource. The sweetness has certainly inspired their rugs!

I spotted this rug in an auction in Berkshire. It was badly described, badly photographed but I knew immediately what I was looking at - an early 20th Century Shekarlu. The estimate was woefully inadequate and I wasn’t anticipating getting it for anything less than five times it’s upper estimate.

After an unsurprisingly ferocious bidding war, I managed to secure the rug and, once I’d collected it, I did a little online research and discovered something quite surprising.

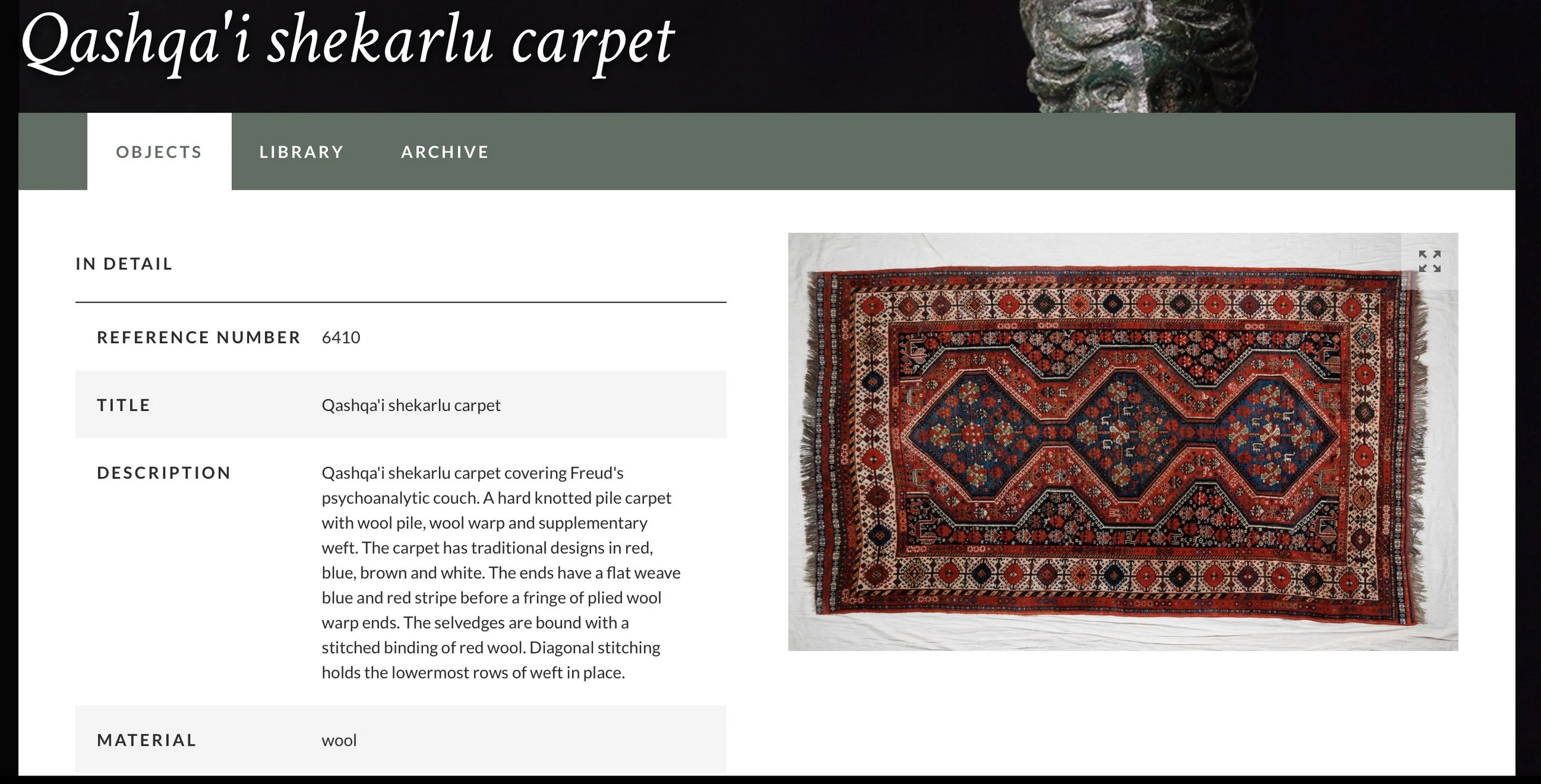

Freud’s couch adorned with an antique Shekarlu rug

I knew that Sigmund Freud, as well as being the father of psychoanalysis, was known to have a bit of a Rug Addiction. What I didn’t know was that he had an antique Shekarlu rug on his couch! His rug, along with other possessions, travelled with him from Vienna to his new home in London in the late 1930s.

Although the central design is different, you can see from the images below that the border design is very similar and classic Shekarlu.

The two rugs have very similar borders

This rug has been sent to my restorer’s for some TLC and a bit of a clean. It will be on my website soon!